20/03 - 9/06/2024

Digitorial® for the exhibition

Her name may sound familiar: Käthe Kollwitz (1867–1945), one of the most famous female artists in German history, but she has all too often been pigeonholed. Whether as a feminist pioneer, a posterchild of the communist cause, a good Christian citizen, or symbol of German post-war reconstruction, the artist has rarely been judged without preconceptions and labels. Yet Kollwitz’s search for new forms of artistic expression at a time of great social change makes her a unique voice in modern art.

1

ONE GOAL

IN MIND

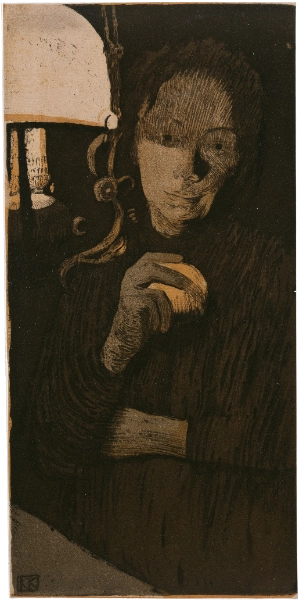

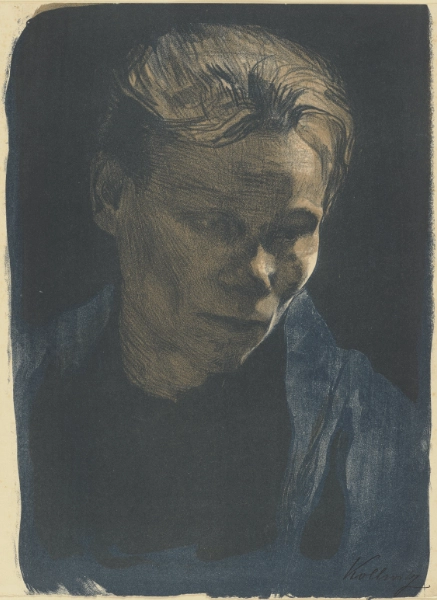

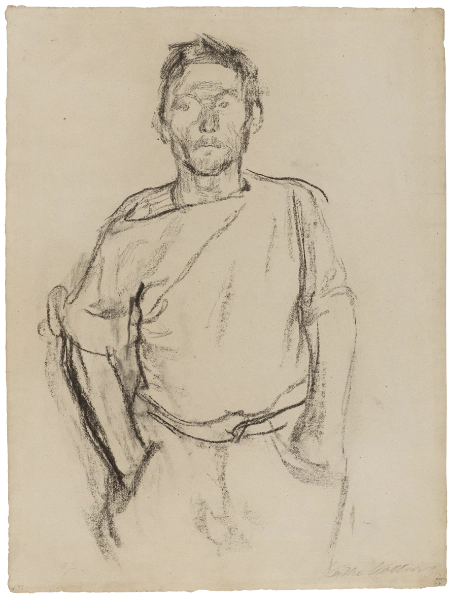

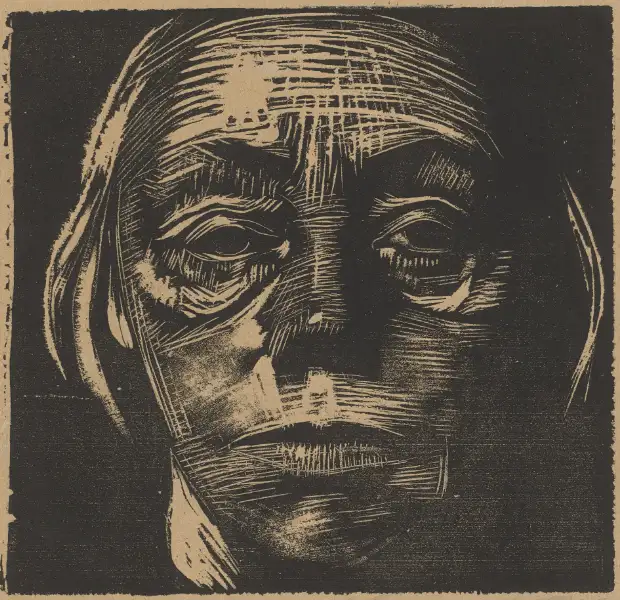

Self-reflection is a common theme in Kollwitz’s work. Her many self-portraits reveal a fierce determination to break new ground as a woman and to claim her place as an artist.

I had a sense of purpose.

Sensitive, a little defiant and curious, at the age of 22, Kollwitz was already aware of her public image. The drawing is unusual for portraits of women of her time: some women may still be seen wearing crinolines, but she is dressed in a plain, functional shirt, her long hair tied back. This is not a traditional representation of femininity; rather, a modern young woman meets the eye of the viewer.

Modernism – A New Start

Modern art should come from the artist’s own observations, and as an artist Kollwitz repeatedly held up a mirror to herself.

Käthe Kollwitz lived through the founding of the German Empire, the 30-year reign of Kaiser Wilhelm II, the First World War, the end of the German monarchy, and the Weimar Republic. In 1945, shortly before the collapse of the brutal Nazi regime, the artist died in Moritzbug, Saxony, after fleeing the bombing of Berlin, where she had lived for most of her life. Her work reflects the individual and a society in troubled times.

An Artist of Her Time

It was almost impossible for a woman of Kollwitz’s generation to become a professional artist, to receive an art education, to pursue her own artistic vision and to establish herself as a creative force. It took fierce determination to follow her passion.

There may well be women with genius traits, but there is no such thing as a female genius, there never has been and there never will be.

For women, equality was a distant reality. Until 1919, women were not admitted to German art academies. It was commonly believed that the female sex was incapable of artistic inspiration and creativity. Instead, young female artists were trained in professional organisations established by women that operated in the shadow of the academies. At the age of 19, Kollwitz took lessons at the all-female painting and drawing school of the Verein der Künstlerinnen und Kunstfreundinnen zu Berlin, which would not have been possible without the help of her progressive parents.

Family Home

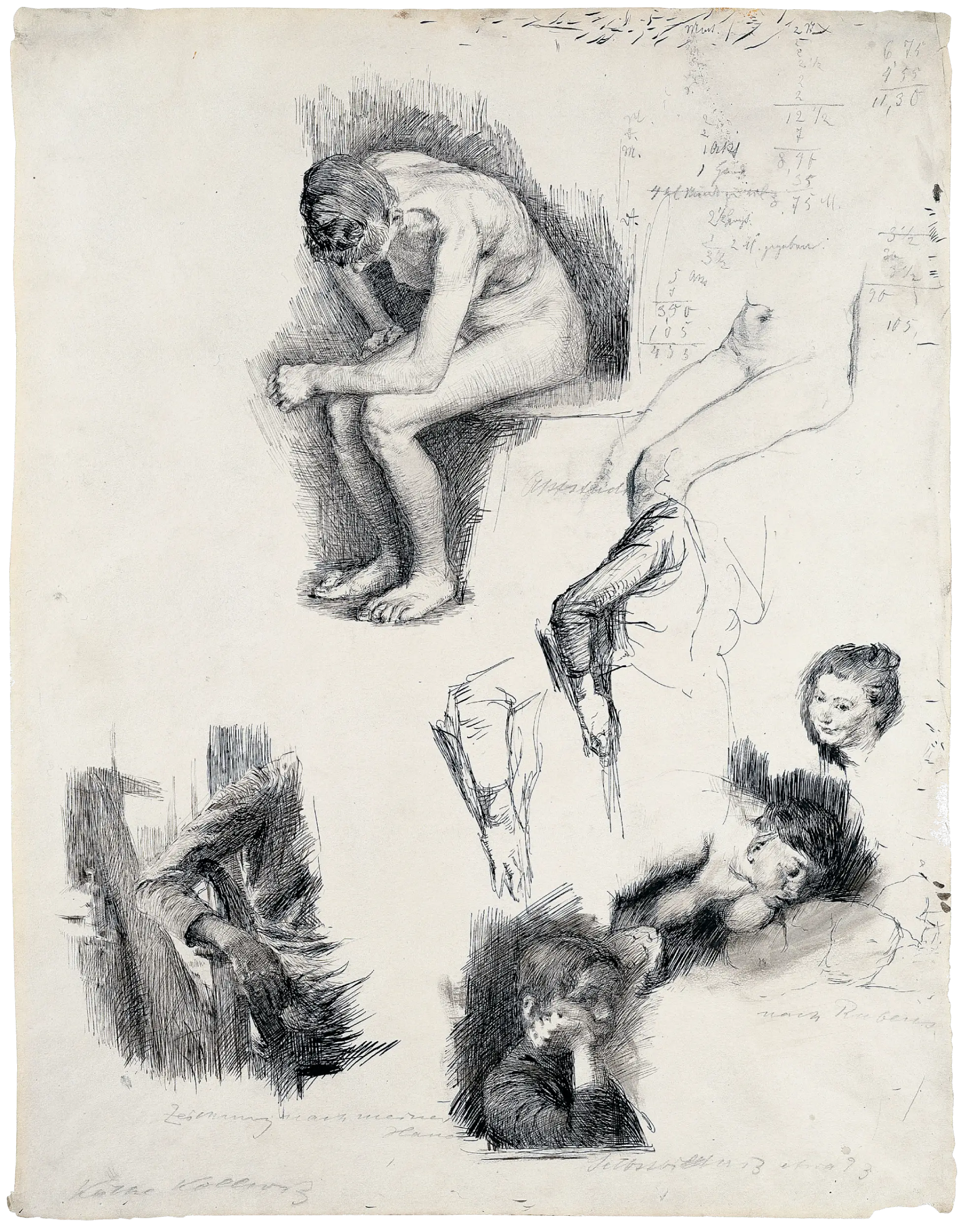

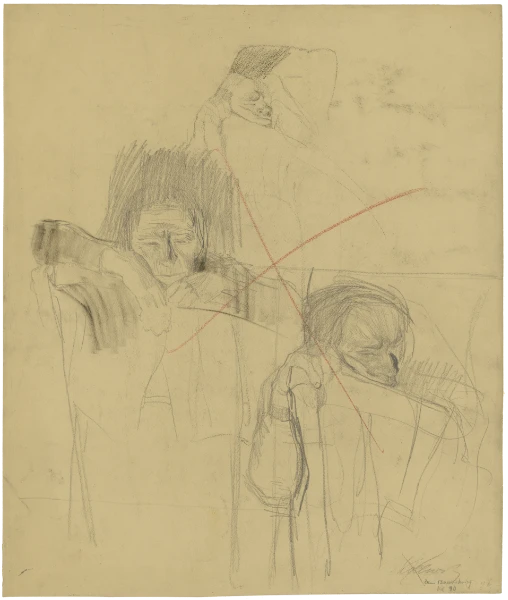

This page from her sketchbook held great significance for Kollwitz until the end of her life. It was a reminder of her training and a testament to her talent. It shows studies after Peter Paul Rubens and, at the bottom centre, a moody self-portrait. In 1888, after a year in Berlin, her father sent the young artist to Munich, where a lively art scene beckoned.

I was enchanted by the free expression of the Malweiber.

„Malweiber“, a mocking term that roughly translates as „[that bunch of] painting maids“, was defiantly adopted by the female art students themselves in Munich. The young women were aware of their social position and, as a provocation, wore painters’ coats out in public. Kollwitz and her colleagues even tried their hand at the new (and decidedly foreign) style of Impressionist painting.

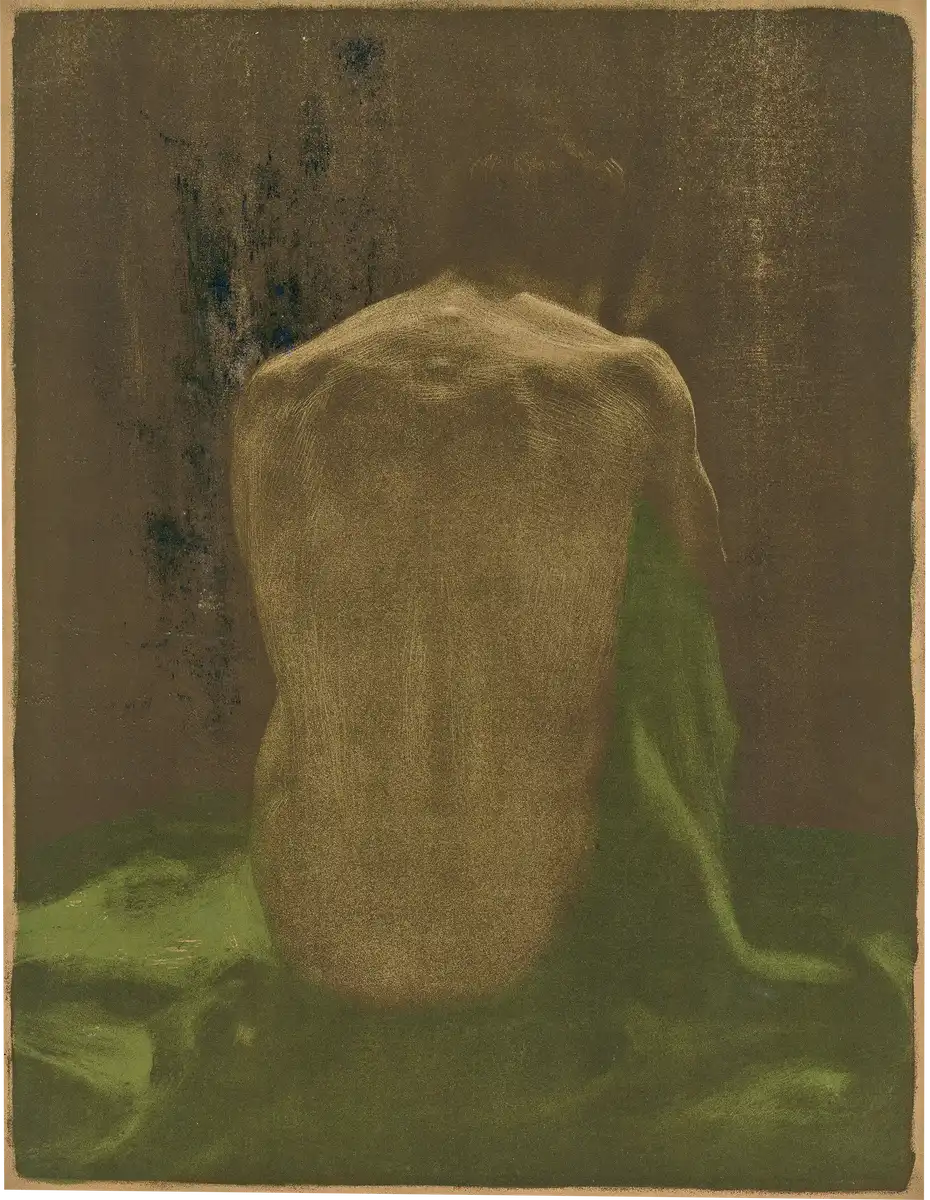

Paintings defined mostly by strong colours and atmosphere would soon be the exception in Kollwitz’s work. Her professor in Munich, Ludwig von Herterich, taught a more desaturated style of painting. By the end of her studies, however, the young artist decided to follow her own artistic path.

2

A RUTHLESS

LINE

In a bold decision, Kollwitz turned her back on painting in 1891. Drawing and printmaking allowed her to achieve greater intensity, and from then on she developed the artistic themes and characteristic style that are still associated with her name.

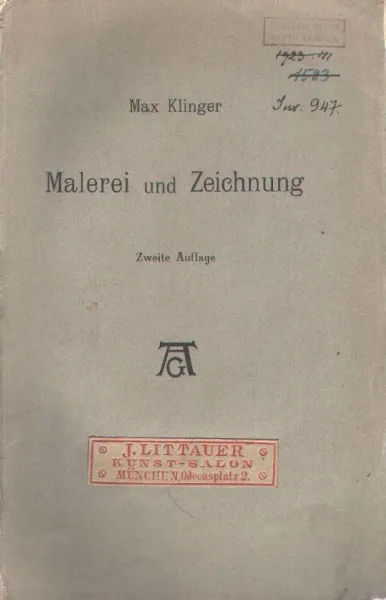

I happened to read Max Klinger’s book ‘Painting and Drawing’. That’s when I realised: I’m not a painter at all!”

Max Klinger, Painting and Drawing, 1891

Sometimes a book can change one’s life. Kollwitz’s decision to concentrate on the graphic arts was inspired by the artist Max Klinger’s book Painting and Drawing. Kollwitz must have read it soon after its publication in 1891.

Where painting would have to offer the spectator […] pure pleasure […] drawing develops a piece of life with all the impressions accessible to us […].

Max Klinger describes the potential of drawing and printmaking as truthful, a direct expression of the artist’s life experience with the potential for great emotional impact. While painting strives for harmony and beauty, graphic art can convey powerful, immediate truths. Klinger’s ideas strengthened Kollwitz’s resolve in her chosen artistic path.

Printing plate as a field for experimentation

Observing, sympathising, and empathising – Kollwitz developed a distinctive visual language in her drawings and prints, depicting scenes which, with unsparing intensity, make the connection between the individual and society. She sought to get as close as possible to the bodies and emotions of the people she portrayed, drawing a clear line between her art and that of her role model, Max Klinger.

The Gretchen Question

Not to suppress or gloss over, but to show. By turning to graphic art, Kollwitz created images that were close to life.

A Closer Look

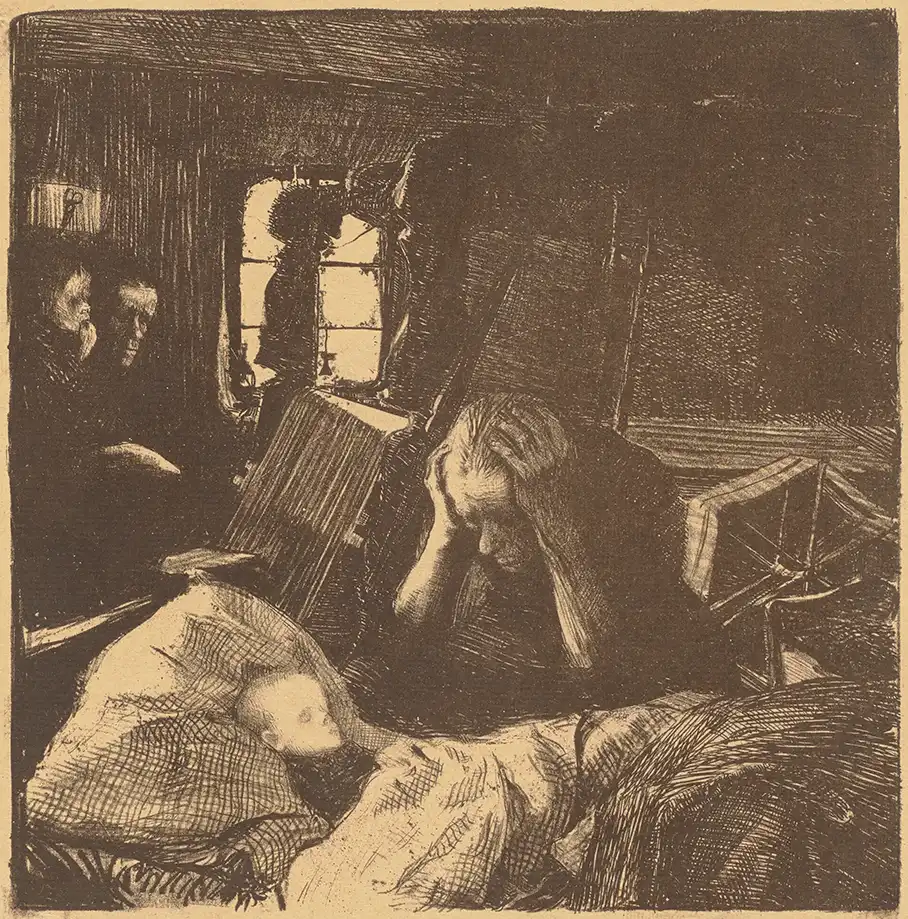

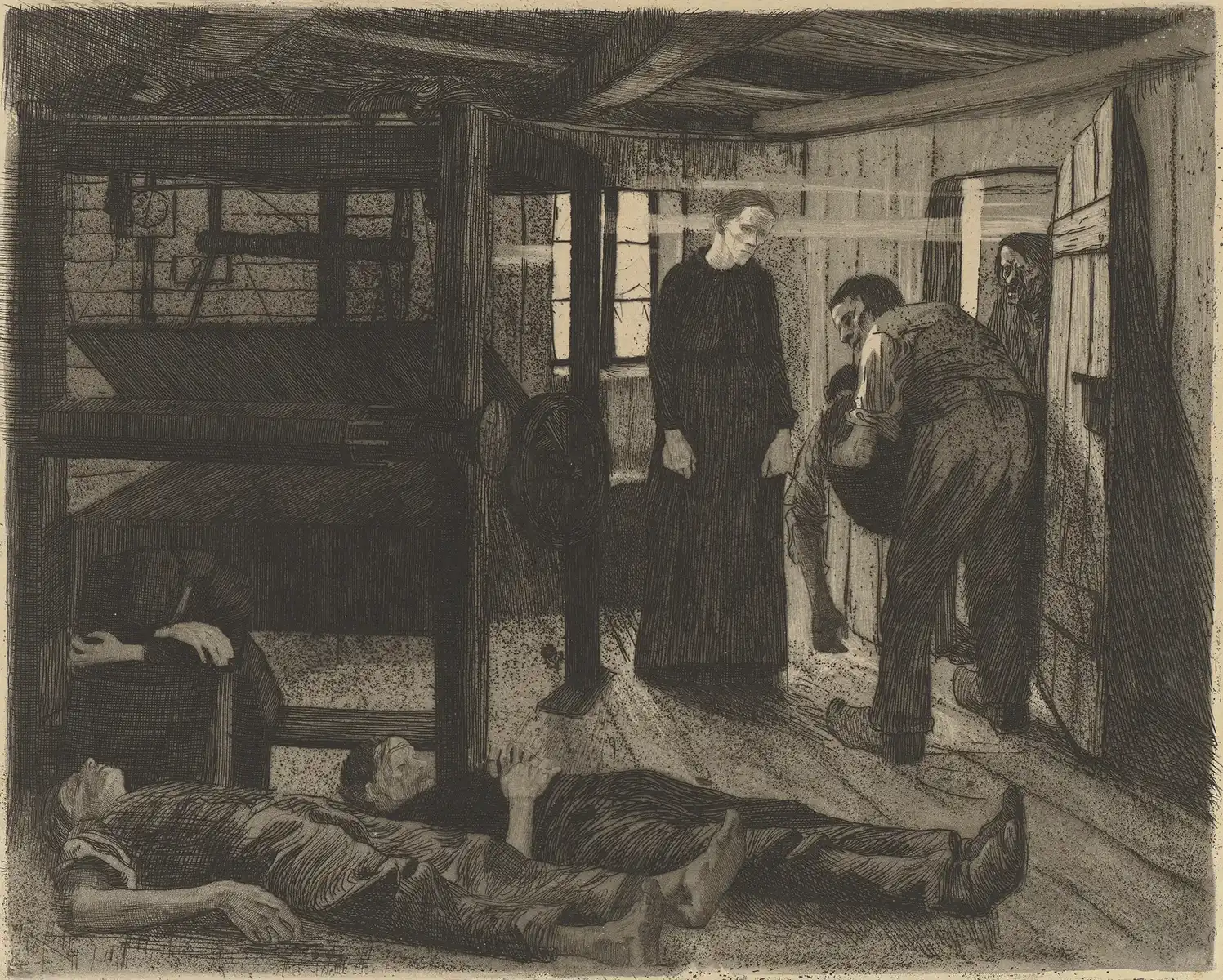

Choosing printmaking paid off: Kollwitz’s six-part cycle A Weavers’ Revolt was a surprise success on the Berlin art scene. Her art was seen to break norms and defy expectations.

Not only the subject matter, but also the powerful masculine characteristic, the boldness of the execution […] contradicted everything that had previously been seen in the visual arts by women.

Impressed by Gerhard Hauptmann’s play The Weavers, Kollwitz set to work soon after attending its premiere in Berlin in 1894. With her series of prints, she ventured into a historical subject that had caused a scandal in the late 19th century.

Social Reality as a Law of Nature

The cycle A Weavers’ Revolt was a success at the 1898 Grosse Berliner Kunstausstellung (the closest thing to the Paris Salon in the German capital) and helped make Kollwitz famous. She was even nominated for a medal, but Kaiser Wilhelm II vetoed it. The Kaiser disapproved of Kollwitz’s unflinching view of misery and deprivation: “gutter art” he called the pictures, because they violated established standards of beauty.

If, as is often the case now, art does nothing more than make misery even more hideous than it already is, then it sins against the German people.

Wilhelm II was convinced that artistic beauty and grandeur should illustrate the morality and greatness of the German Empire. Kollwitz’s austere aesthetic and her strong commitment to social issues deliberately went against the grain. She became part of the emerging artistic movement of modernism, which sought to break out of the narrow corset of academic and state-sanctioned art.

3

INSPIRING

CHANGE

The aim of artists’ collectives throughout Europe was to give artistic expression to new freedoms and to bring art closer to life in the modern age. As a member of the Berlin Secession, Käthe Kollwitz was part of an international network of artists, in a time of strident nationalism. She found inspiration in Paris, the city of art.

Is it necessary or reasonable to lament that the end has come for old, outdated art forms? They are too old, too frail to take in what is supposed to come to light through them: a new art of a new age.

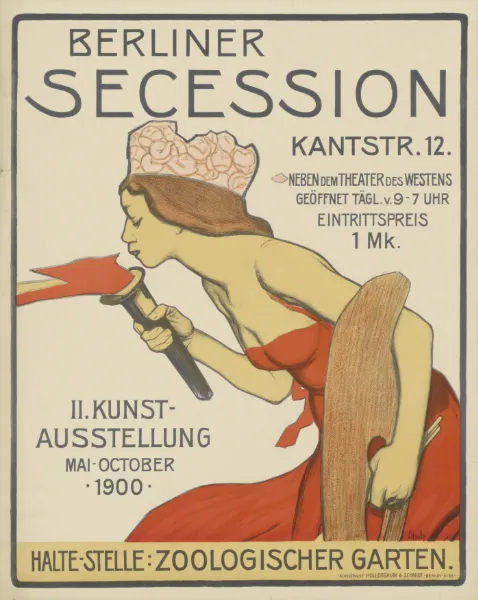

Kollwitz took part in the first exhibition of the Berlin Secession. In 1901 she became a full member of the group, which had been founded in 1899 as an antipole to the academic art establishment of the German Empire. Woman, wife, mother of two, and an active artist – she remained exceptional even by the standards of the progressive art scene.

Secession means “breaking away”

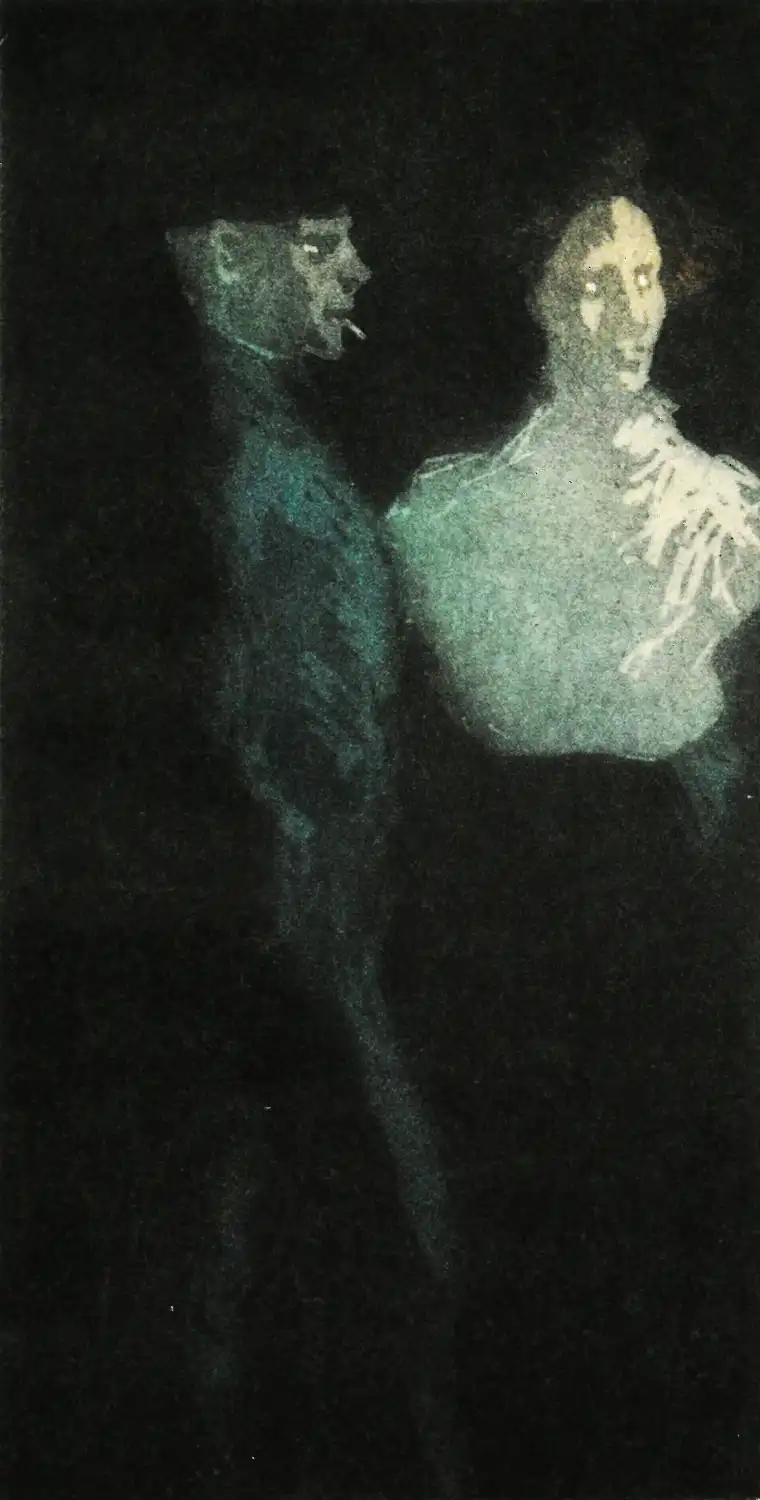

Dance, music, literature – new forms of expression were revolutionising all areas of culture, and Kollwitz was at the centre of it all. Her stunning work La Carmagnole, which she unveiled at the Berlin Secession exhibition in 1901, is a testament to this.

At the time, Kollwitz described La Carmagnole as her key work. She took an impression of it with her on her first trip to Paris in 1901.

The Colours of Paris

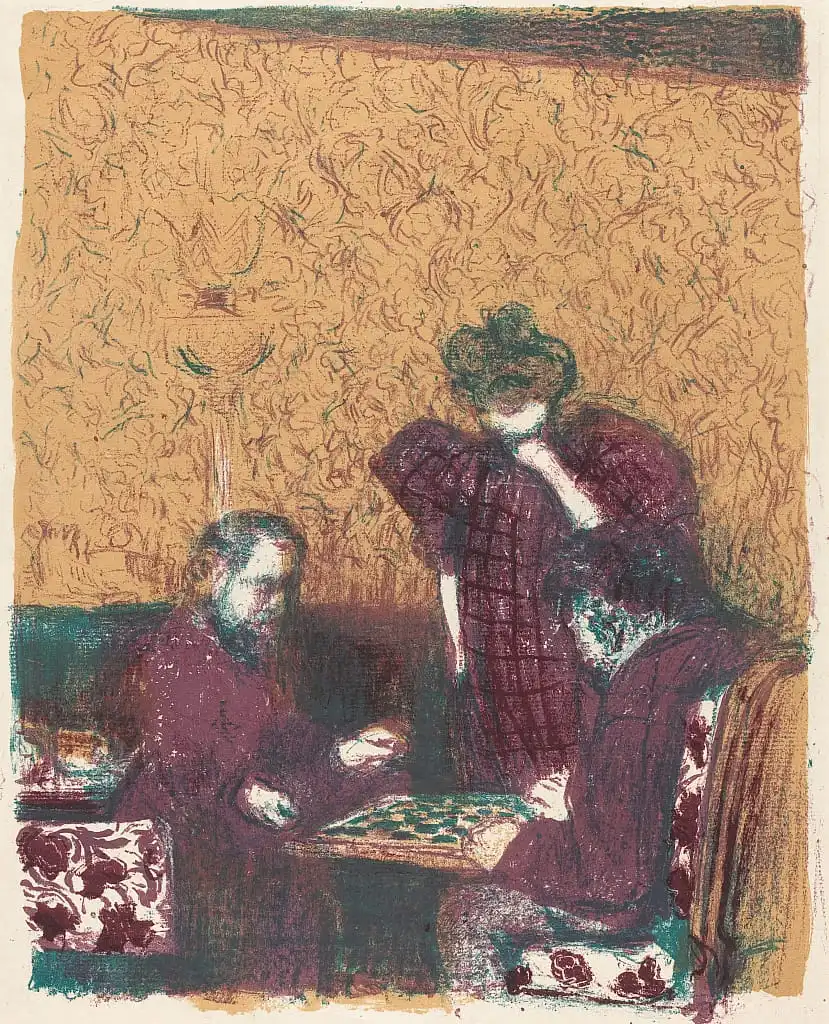

Cosmopolitan Paris cast a spell over Kollwitz. Her visits in 1901 and 1904 exposed her to art that had never been shown in Berlin. From then on, she kept a close eye on the international currents of modern art.

Paris enchanted me...

Depicting life in a modern industrial society required an appropriate artistic language: expressive, rough lines, flat planes of colour and the technique of colour lithography – Kollwitz drew inspiration from a wide range of influences.

New combination

I hope my work will reflect what I took away from Paris.

Honest Workers

The proud achievements and pitfalls of industrial urban life: Kollwitz sharpens her penetrating view of contemporary society. Her depictions of the working class are as compelling as they are unique.

The many quiet and loud tragedies of life in the big city – all this together makes this work extraordinarily dear to me.

Around 1900, modern artists made the subject of industrialised labour socially acceptable: Hans Baluschek in Berlin and Pablo Picasso in Paris turned their attention to the people who toiled on the outskirts of the city or were pushed into unemployment and poverty.

Exposing social injustice wasn’t the only thing that motivated bourgeois artists. They also painted factory workers because they saw in them an eternal image of honesty, simplicity, and authenticity.

Modernism Yearns for the Simple Life

Such a working-class woman shows me more of her personality and nature than the lady who is constrained by convention in everything she does; she also is far less guarded in the way she expresses her emotions.

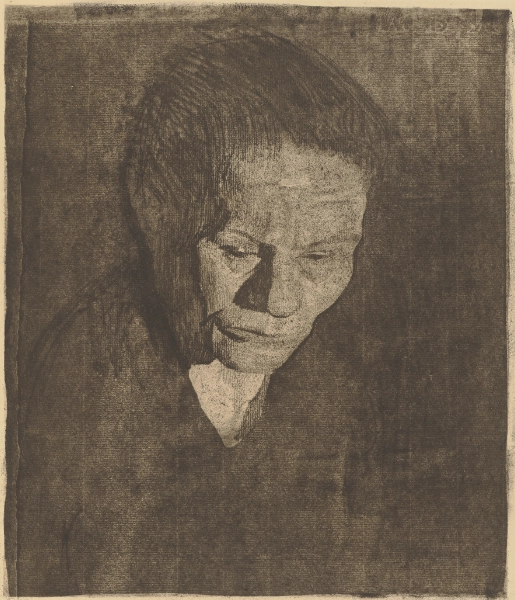

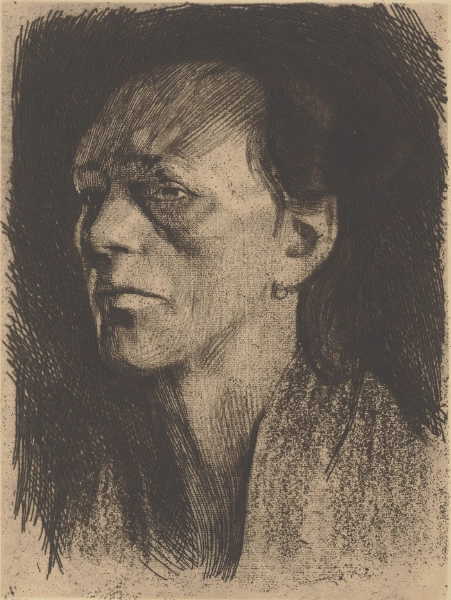

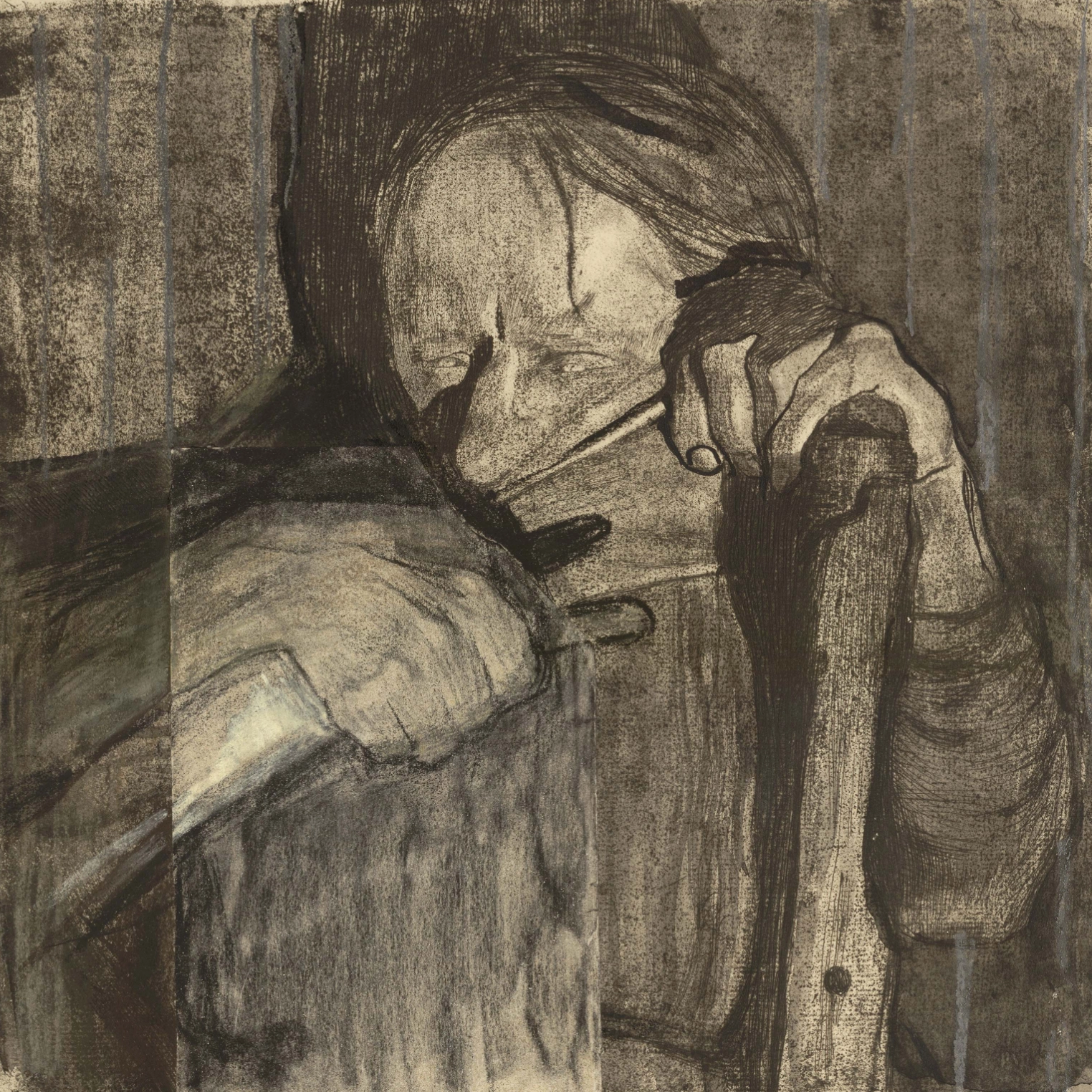

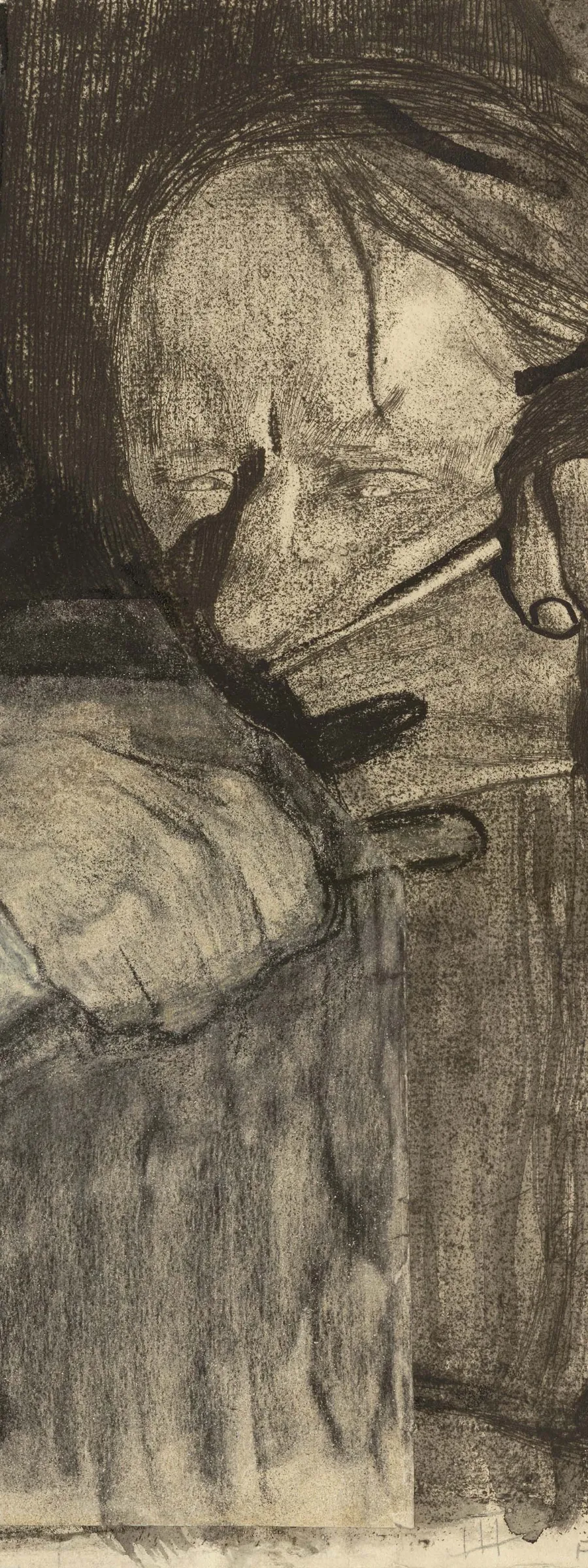

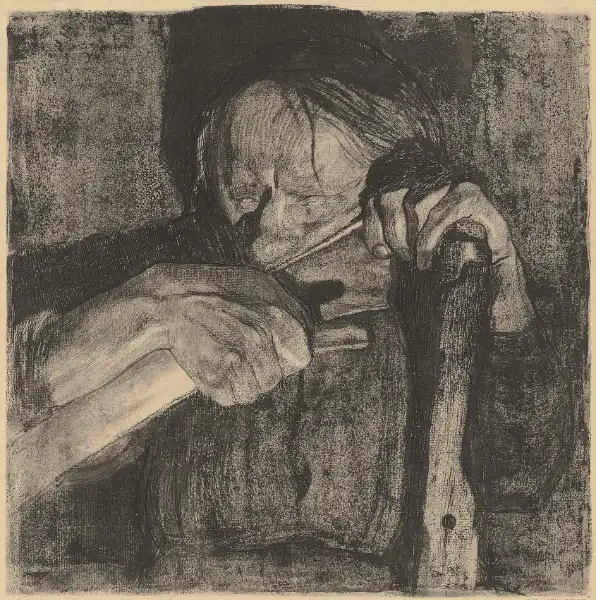

At first, Käthe Kollwitz thought she saw an unconventional beauty in the perceived naturalness of working-class people. But her Heads, which date from the first decade of the 20th century, already stood apart from other modernist depictions of manual labourers. Kollwitz focused her art exclusively on the faces. They illustrate, individually and at the same time representatively, the effects of social conditions on human beings.

Too close for comfort – to this day, Käthe Kollwitz’s prints have the power to shock. Her art challenges us to take a closer look at things we might not wish to see.

Too Unsightly for the Empress

I was tormented and distressed by unsolved problems such as prostitution and unemployment […]. By depicting them again and again I found an outlet, a way to make life bearable.

4

SCALING

THE LIMITS

Works that are etched in our minds! For Kollwitz, an unflinching examination of society and the search for existential truths about humanity went hand in hand. Again and again, she probed the very limits of the representable.

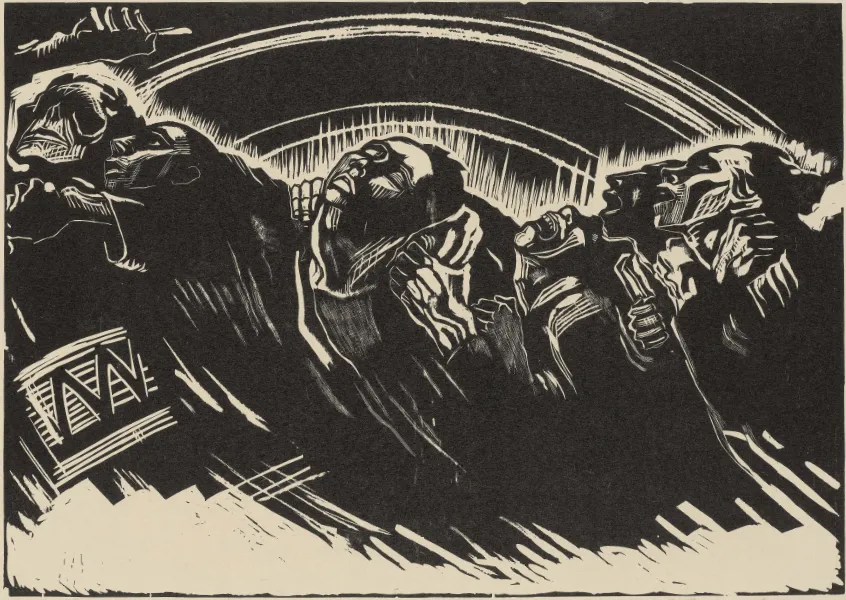

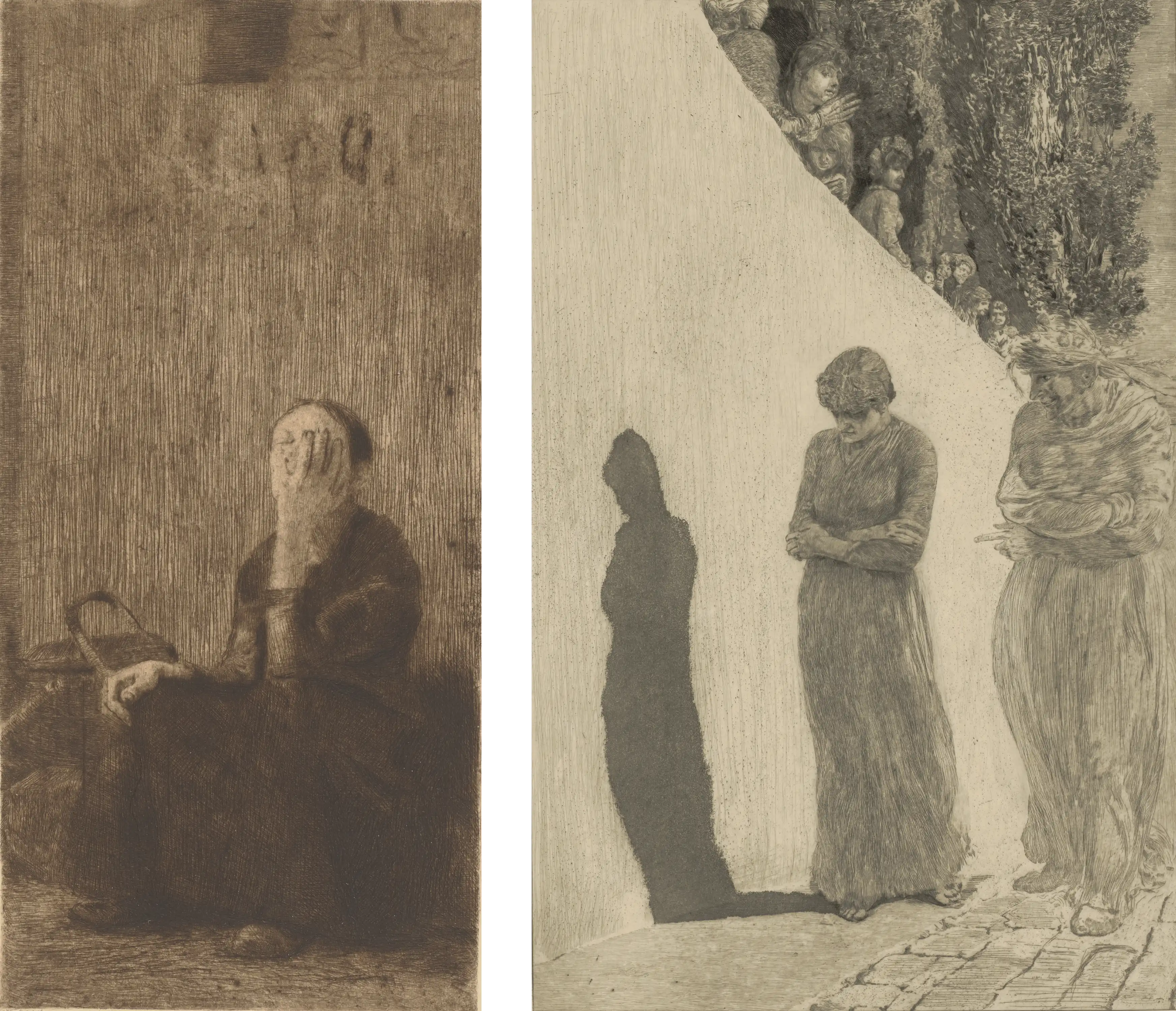

Mensch, werde wesentlich!

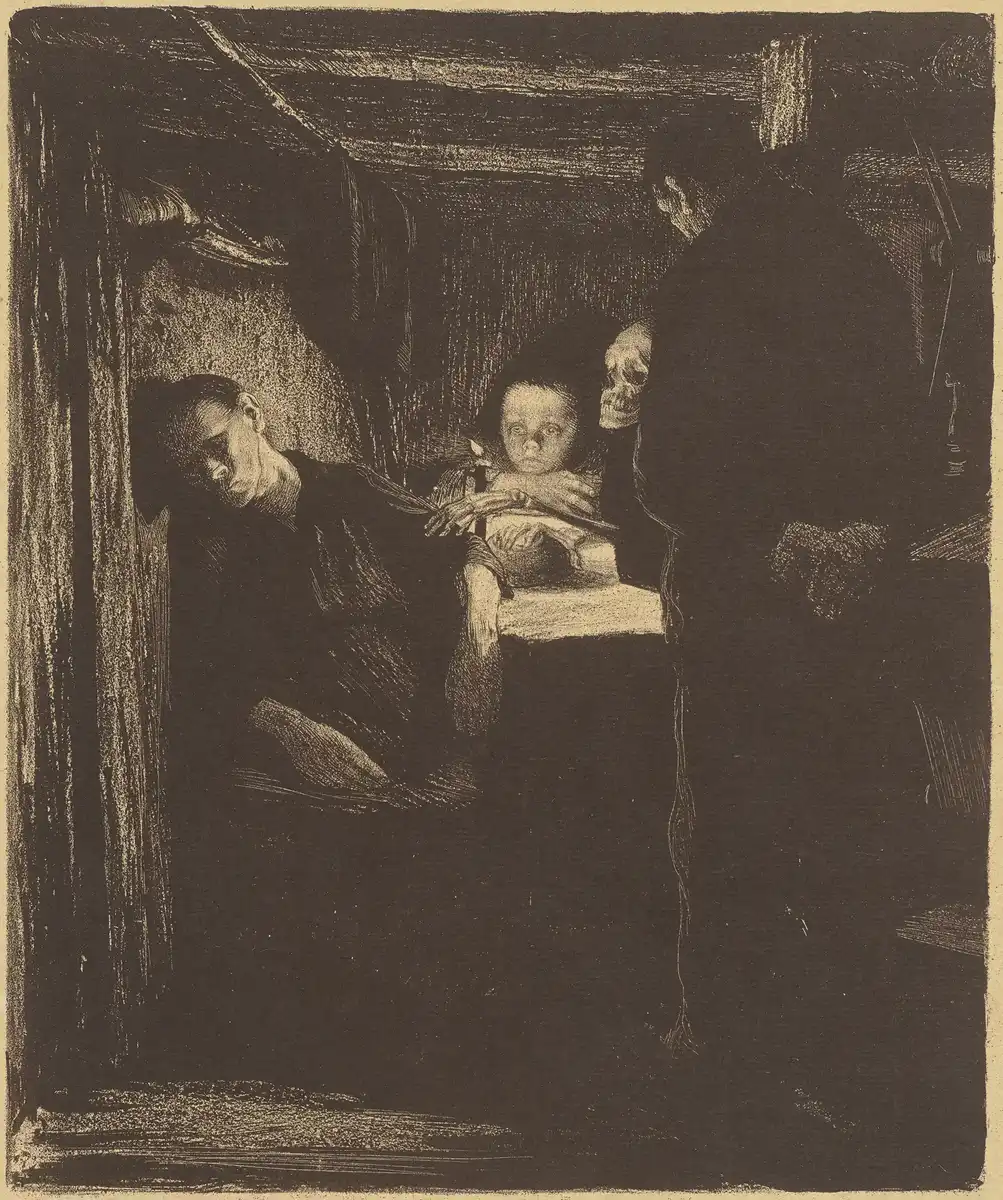

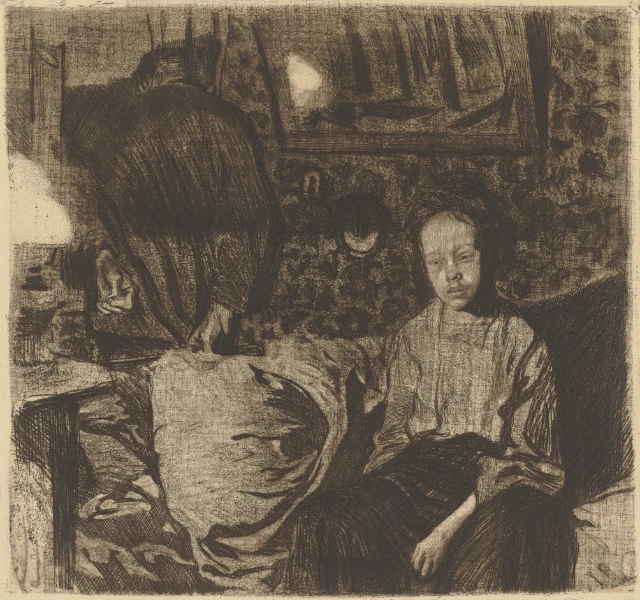

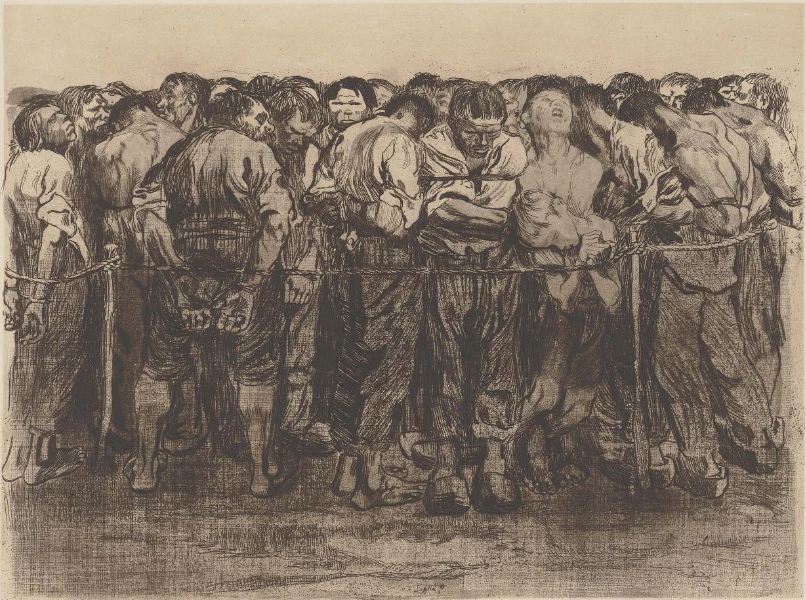

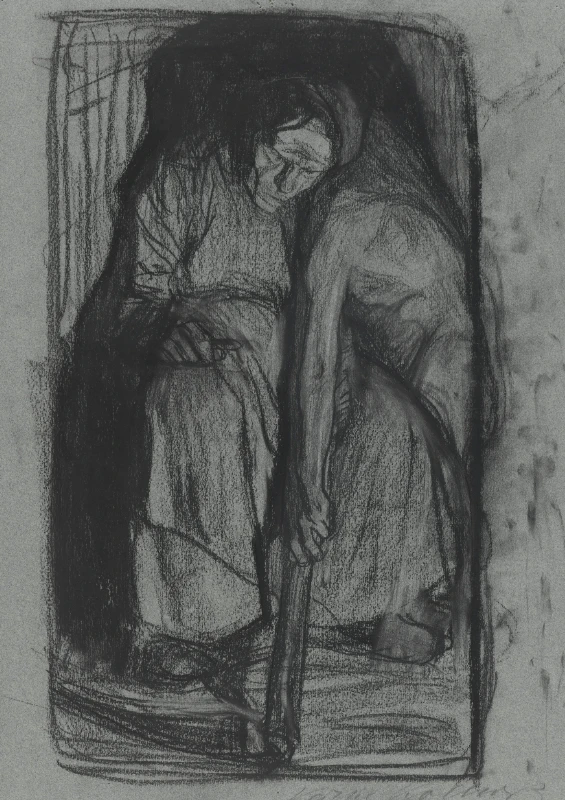

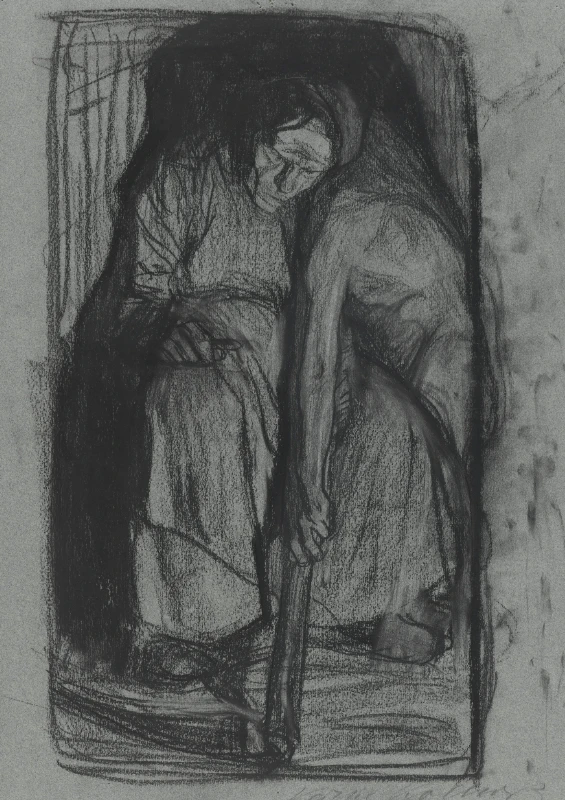

Technically demanding and extraordinarily inventive: Kollwitz’s celebrated cycle Peasants’ War (or Peasants’ Revolt) makes a powerful impression. For seven long years, between 1901 and 1908, Kollwitz struggled with these seven compositions. The result was a penetrating depiction of a desperate insurrection by downtrodden people.

The cycle depicts the German revolt known as the Peasants’ War (1524/25). The struggle by the peasantry to overturn serfdom, feudalism, and the vassalage entailed by the system of the Estates was regarded by many 19th-century historians as the most important liberation struggle in the whole of German history.

Revolution of the Common Man

Physical and sexual degradation, collective rage, unfathomable sorrow, profound resignation: in The Peasants’ War, Kollwitz confronts us with a spectrum of emotional extremes. The historical events of the 16th century become a template for a timeless warning against the violation of human dignity.

A tense, delusional, yet fully absorbed state of consciousness, “on the razor’s edge”: sheet 3 of the cycle, entitled Sharpening the Scythe, is one of the artist’s boldest inventions. But the path leading toward this unsettling depiction of a peasant woman was protracted. In numerous drawings and proofs trying out a variety of techniques, Kollwitz cautiously approached this final version.

I hope to present it in such a way that I can finally be finished with it.

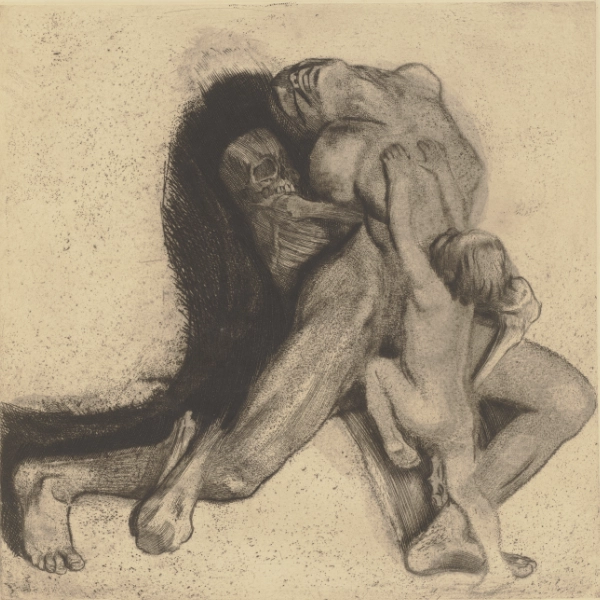

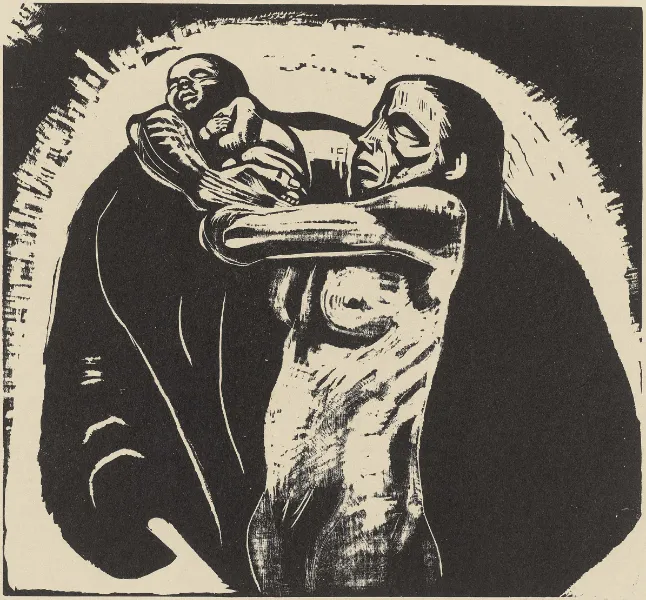

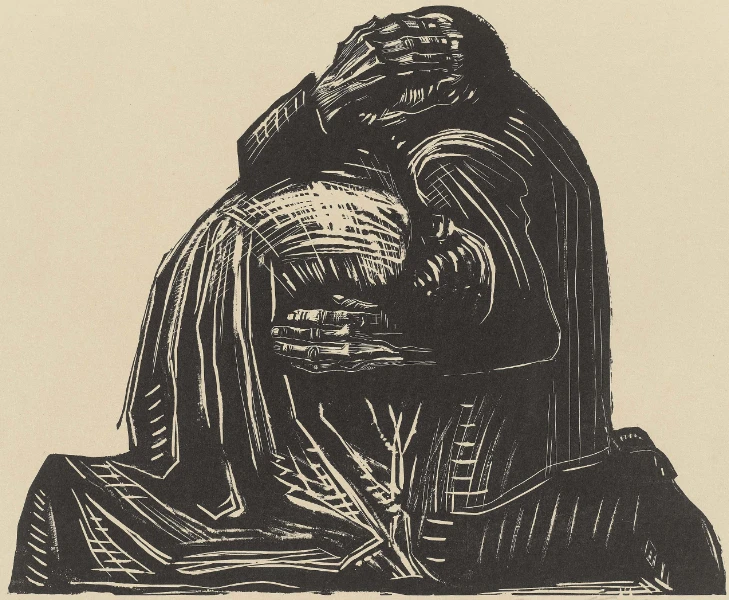

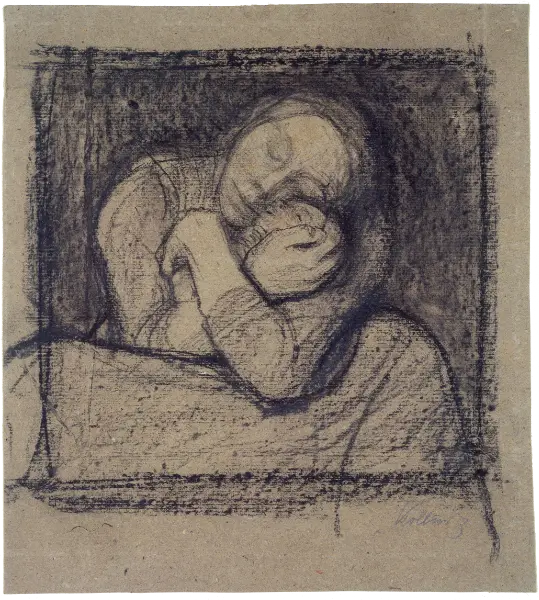

Kollwitz worked processually: as a modernist, she struggled with form. Having devised a certain motif or composition, she would reuse it for many years. This was true as well for a subject that would accompany her – stalk her – throughout her life as an artist: the mother with her (dead) child.

Mother, Body, Person

Images when there are no words: an etching that shocks the viewer to the core. A mother clasps the lifeless body of her child.

Inexpressible passion, inconceivable pain: the bodies of mother and child fuse to form a unity. The transformation of the mother seems almost animalistic: she lowers her face onto the breast of her dead child, inhaling, unwilling to let go.

Working through tears

To love, to be forced to part with the beloved, holding on – always the same thing. Why is it that for years now, many years, the same subject is repeated again and again in my work?

Motherhood as an existential experience was a core theme in Kollwitz’s art over a period of at least three decades – in drawings, etchings, lithographs, and finally in bronze. Kollwitz continually transformed one of the most frequently encountered motifs in the history of European art – the mother with a child – into new, modernist pictorial conceptions. She depicts bodies in intimate embraces, in intense contact with one another, conveying the ‘boundary situation’ that motherhood can be.

Hard bronze – soft bodies: as early as the 1910s, Kollwitz attempted to translate the motif of motherhood into a bronze figure. Only in 1936 did this project reach its conclusion: the figure of the mother is circumscribed by rounded forms, she clasps two children firmly in her lap. A powerful and timeless gesture of protectiveness that is simultaneously reminiscent of the birthing process.

From Paper into Space

Motherly love – one of the strongest emotions for Kollwitz, and one that touches the very core of human existence. With great immediacy, her art confronts us with a harsh reality: love for a child is inseparable from fear of loss and death.

As an artist, I have the right to extract the emotional content from anything.

5

AGAINST WAR

The final thirty years of Käthe Kollwitz’s life and artistic career were shaped by two world wars. The experiences of grief, loss, and profound shock are mirrored in her works. Kollwitz became an impassioned pacifist.

I have no trouble with the idea of my art serving a purpose. I want to have an impact at a time when people are so baffled, so in need of help.

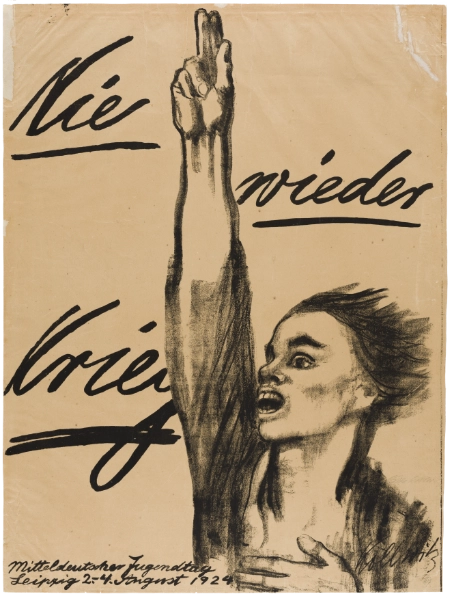

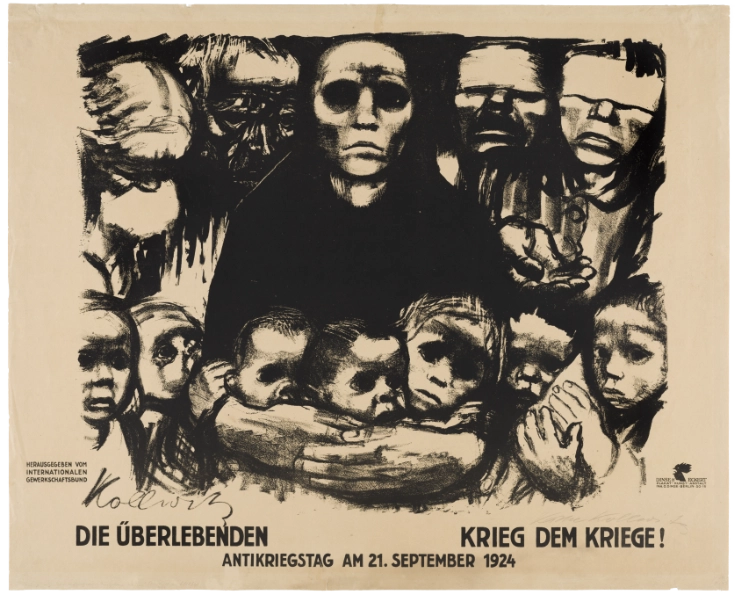

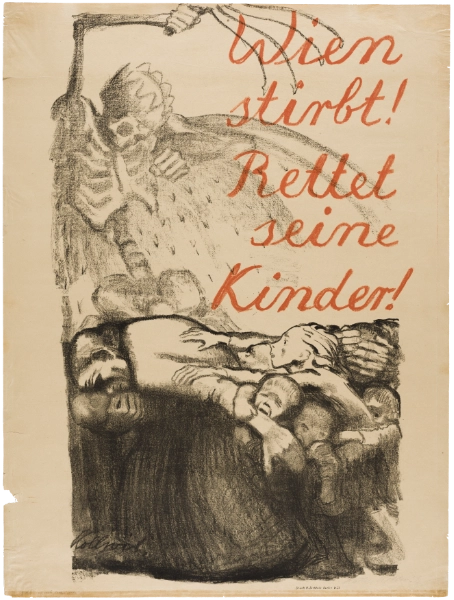

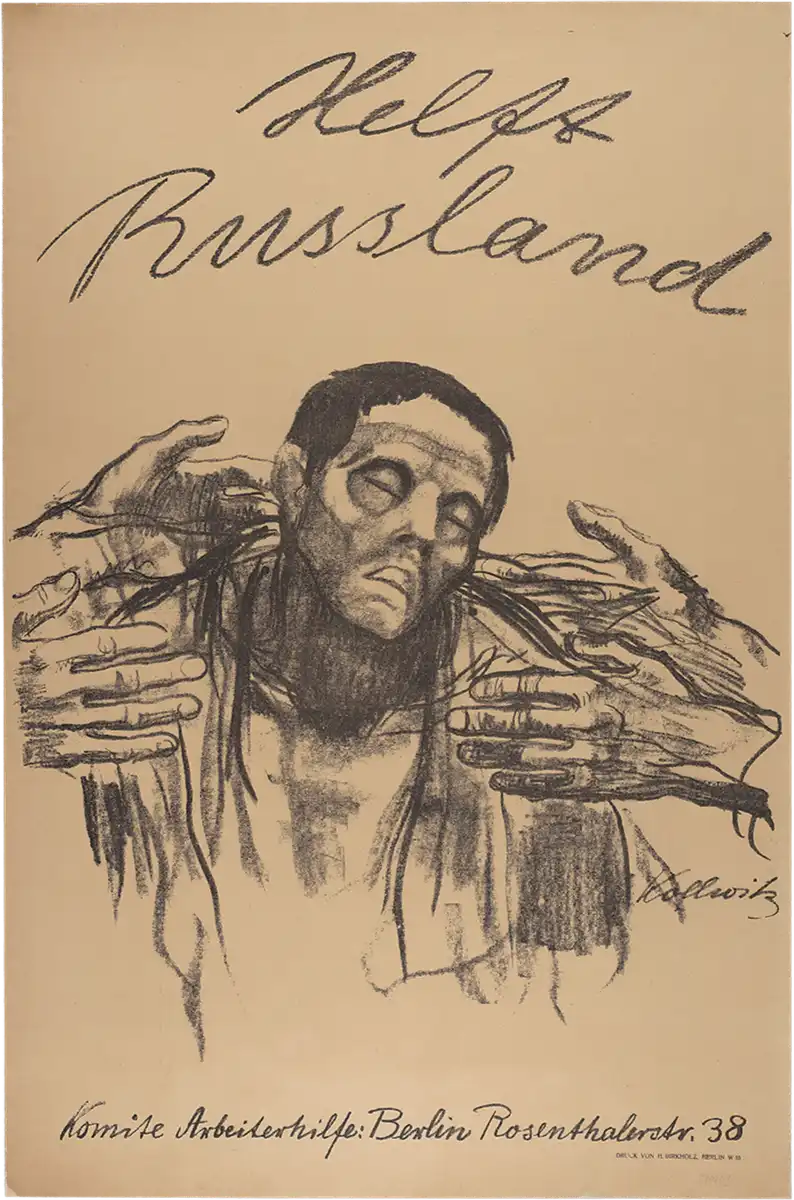

Art on posters? Again and again, Kollwitz used her striking visual language for sociopolitical purposes. During the interwar period, the years of the Weimar Republic, she was showered with commissions, and worked mainly for left-wing parties and associations.

Kollwitz was a pacifist – as shown by her strident antiwar posters. But it wasn’t until the painful experiences of World War I that she became an ardent opponent of militarism and war. Before then, like many modernists of her time – not just in Germany – she had shared a faith in the putative ‘cleansing’ power of war to do away with the old. Kollwitz once believed that the individual had to make sacrifices, initially agreeing with the war as “just”.

During that period, I, too, experienced a sense of renewal within myself. It was as though none of the old values would endure […]. I experienced the possibility of free sacrifice.

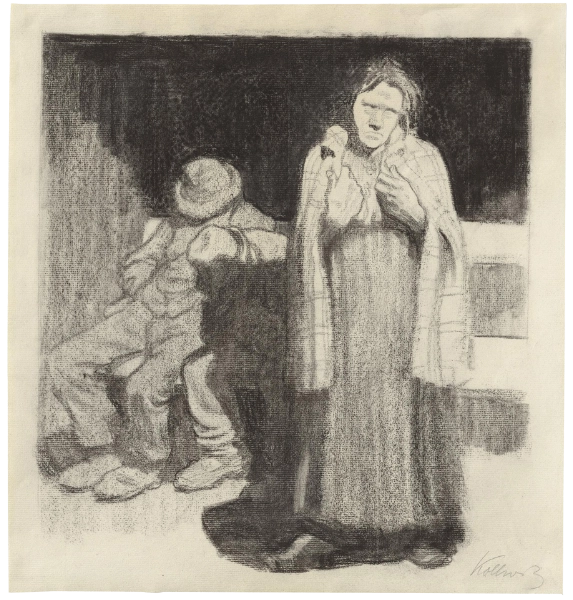

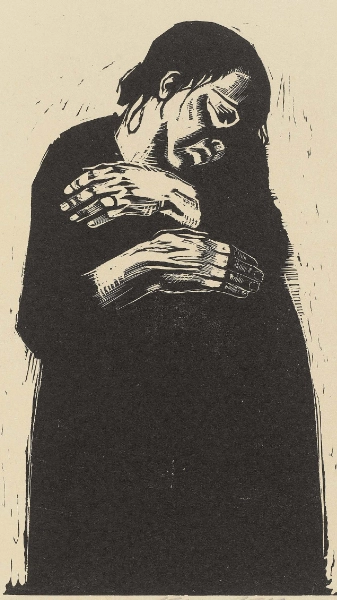

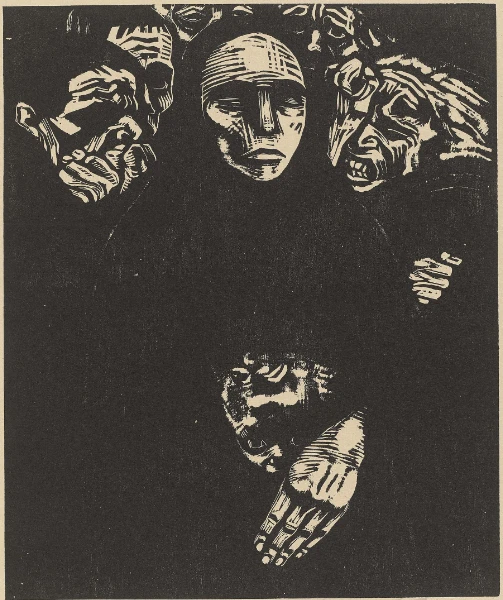

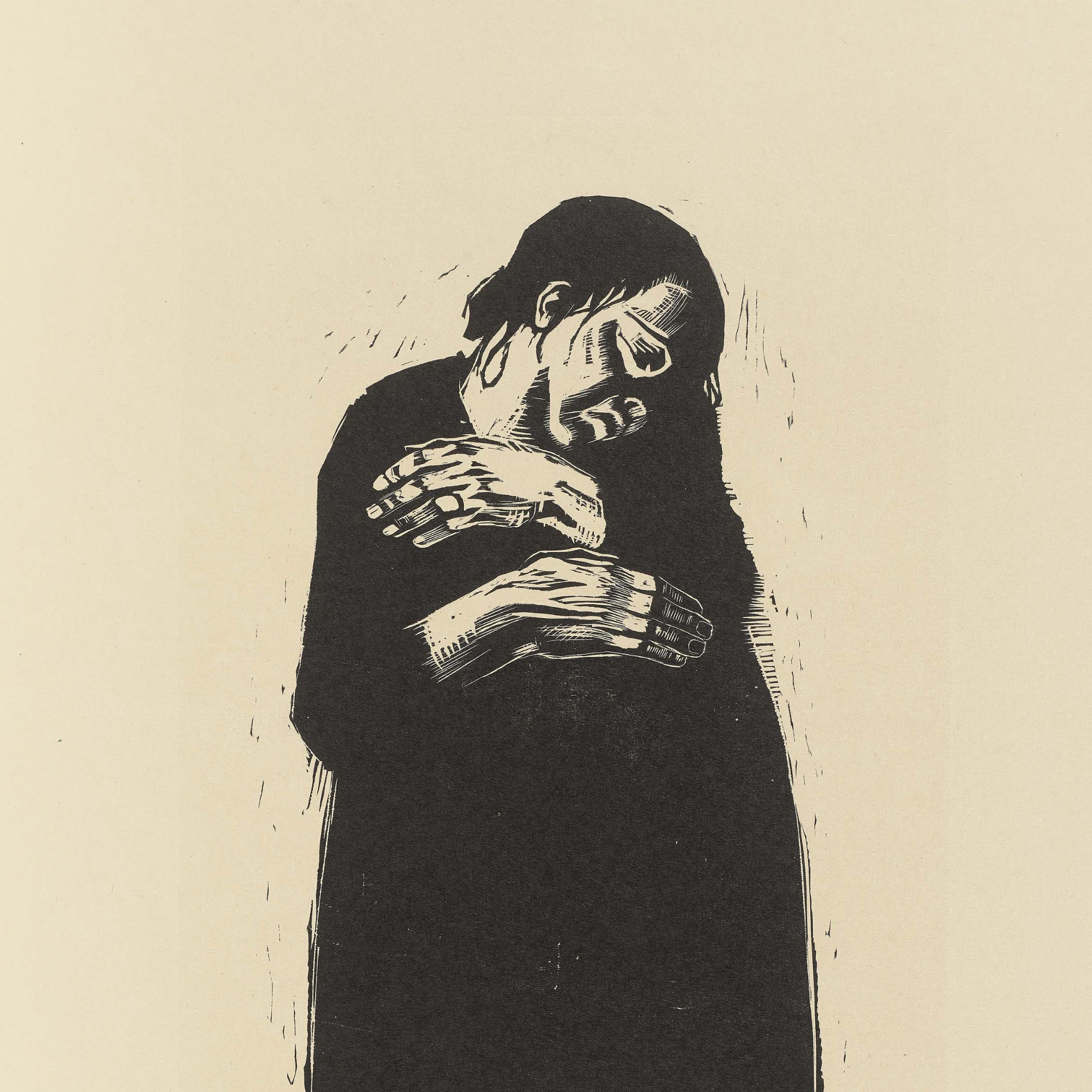

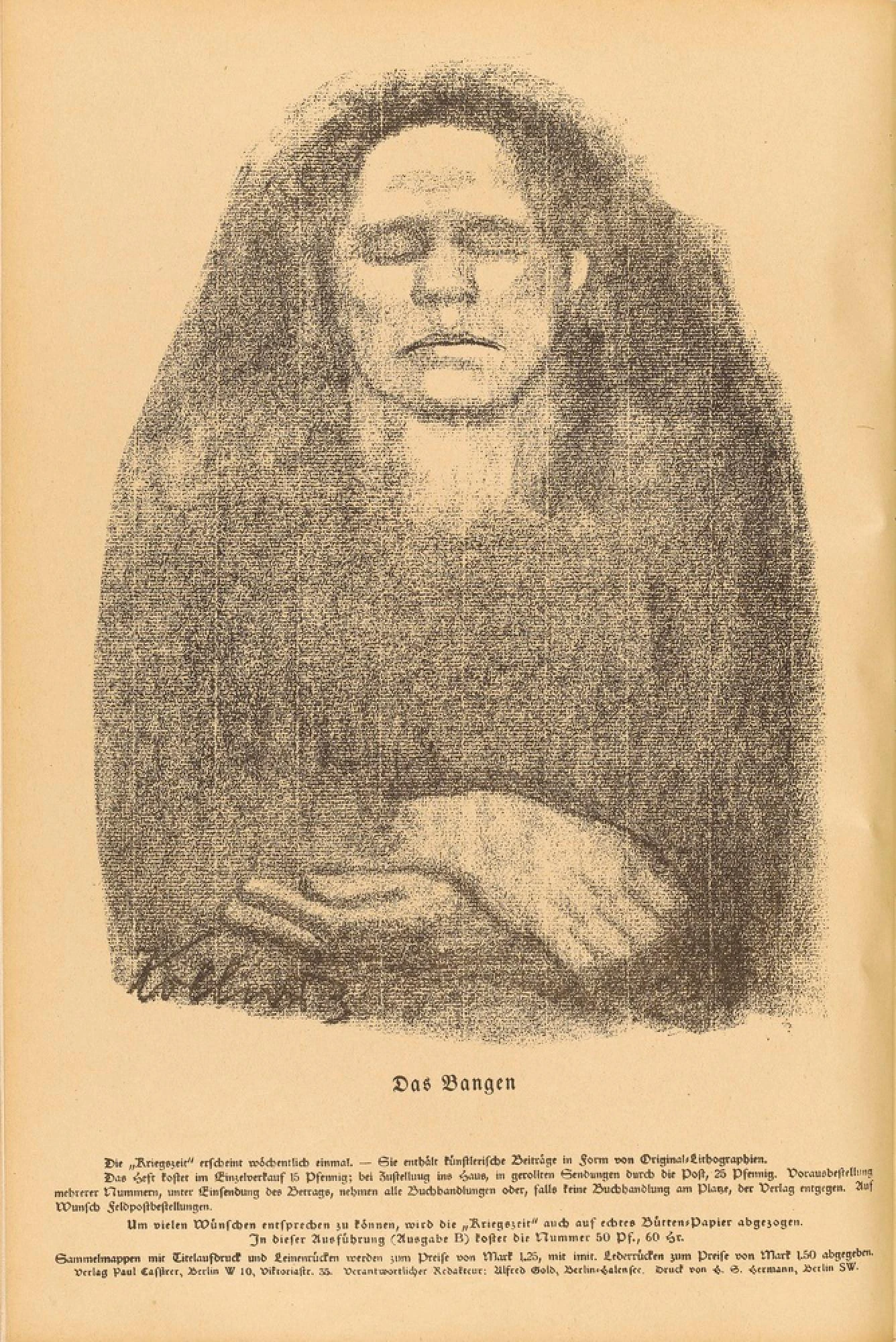

A woman frozen stiff with anxiety: Fear is Kollwitz’s contribution to the magazine Kriegszeit, edited and designed by artists associated with the Berlin Secession. The image betrays the artist’s incipient doubts about the war that had started to form in her mind by October of 1914 – just months after the outbreak of hostilities. Two days after this image appeared, Kollwitz learned that her younger son Peter had fallen – during the march of the German army through Belgium, an act of lawless aggression.

Kriegszeit

Until the End

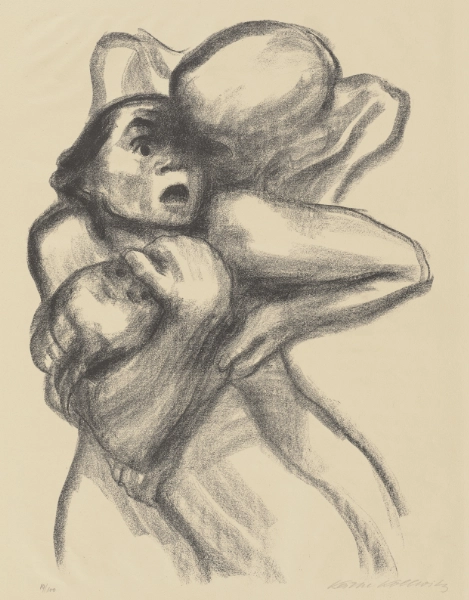

The loss of one’s own child: something Kollwitz had addressed in her art for many years now became a reality in her own life. In order to translate her suffering into images, she sought a new mode of expression.

I always attempted to visualize war. But I couldn’t fathom it. Now, finally, I’ve completed a series of woodcuts that say, to some extent at least, what I wanted to say.

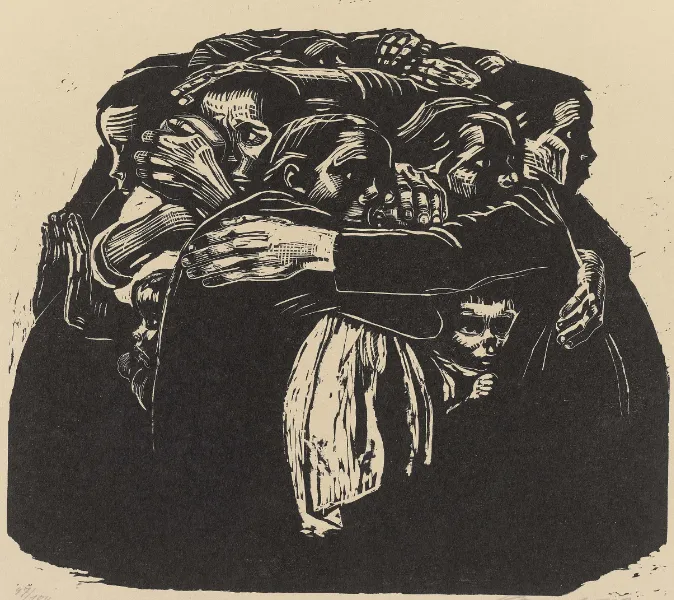

In the medium of the woodcut, Kollwitz found her artistic voice again. Using stark black-and-white contrasts, the series War depicts the human catastrophe of World War I.

Virtually no other artist confronted the experience of World War I with the intensity of Käthe Kollwitz. Her courage to look squarely at things others would prefer to repress accompanied her through this difficult time.

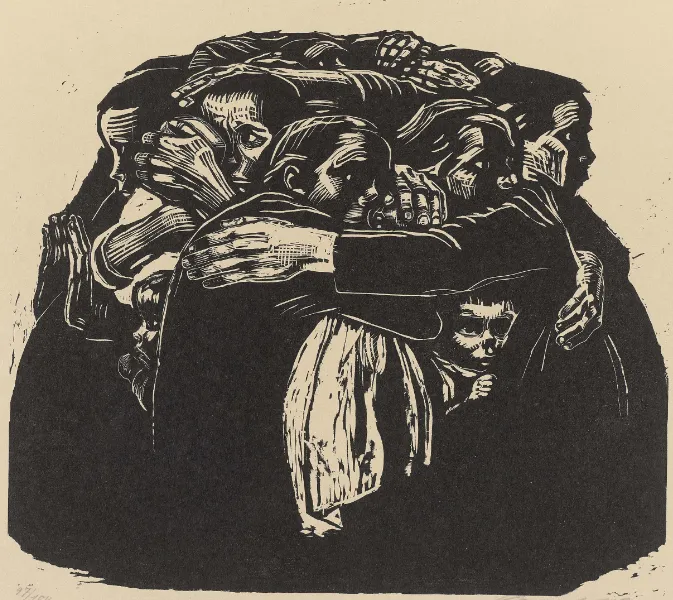

Like a foreshadowing: with infuriated resolve the mothers position themselves protectively before their children. In 1938 Kollwitz completed the bronze sculpture Tower of Mothers – just months before the outbreak of World War II. As early as 1922, she had explored the idea of translating the woodcut The Mothers from her cycle War into three dimensions. The result remains interpretable as a memorial – to the millions of lives extinguished during two industrialized world wars.

The war follows me to the grave.

Käthe Kollwitz’s perhaps best-known work, too, has become a memorial: her Pietà, completed in 1939, has stood in the Neue Wache in Berlin since 1993 as the Central Memorial of the Federal Republic of Germany. Realized in various dimensions, it is dedicated to “the victims of war and tyranny”: a controversial and highly public location for one of the artist’s most intimate works.

She was Käthe Kollwitz, and that’s that.

Unflinching and unsparing: the art of Käthe Kollwitz continues to challenge and shock, even today. All too often over the course of 20th-century history, the name Käthe Kollwitz has elicited stereotypical notions. All the more reason why a prolonged, unbiased view of her artistic legacy is called for and is so rewarding. A closer look at her drawings, prints, and sculptures offers insights into what it means to be an individual in modern-day society.

Hint

Only with the originals do we truly experience the powerful magnetism of Kollwitz’s imagery. Taking shape in the eye of the beholder is a living and breathing web of lines, patterns, and planes. The figures flex and stretch, staggered in relation to one another. When we view this sheet from The Peasants’ War in the original, the surging throng seems to rise up from the flat surface of the paper into our space, as if in relief. A visual experience that is well worth a visit to the museum.

Sponsored by

This Digitorial® was developed by the Städel Museum, Frankfurt/Main, with kind support of the Aventis Foundation. Digitorial® is a product line of the Städel Museum.